Robert Adams (American, 1937 – )

Robert Adams (American, b. 1937)

Self-Portrait on the Pawnee Grassland, Colorado

1983

Gelatin silver print

The quiet of the great beyond

With gratitude, I admire the photographs of Robert Adams. I admire their perspicuous (“clear, lucid”, able to be seen through) and perspicacious (“keen, astute,” able to see through) nature.

They imbibe (“absorb, assimilate,” ideas or knowledge) in us “the wonder and fragility of the American landscape, its inherent beauty, and the inadequacy of our response to it… [they] capture the sense of peace and harmony that the beauty of nature can instil in us – “the silence of light,” as he calls it… [and they] question our silent complicity in the desecration of that beauty by consumerism, industrialisation, and lack of environmental stewardship… While these photographs lament the ravages that have been inflicted on the land, they also pay homage to what remains.”

Like so many photographers of the American landscape, Adams’ debt to the vision of Walker Evans can be seen in his early work, in images such as Movie Theater, Otis, Colorado (1965) and Catholic Church, Summer, Ramah, Colorado (1965) – but even in images such as Wheat Stubble, South of Thurman, Colorado (1965) we can begin to see the beginnings of Adams personal artistic signature, the quiet of “the great beyond” (both physically and spiritually).

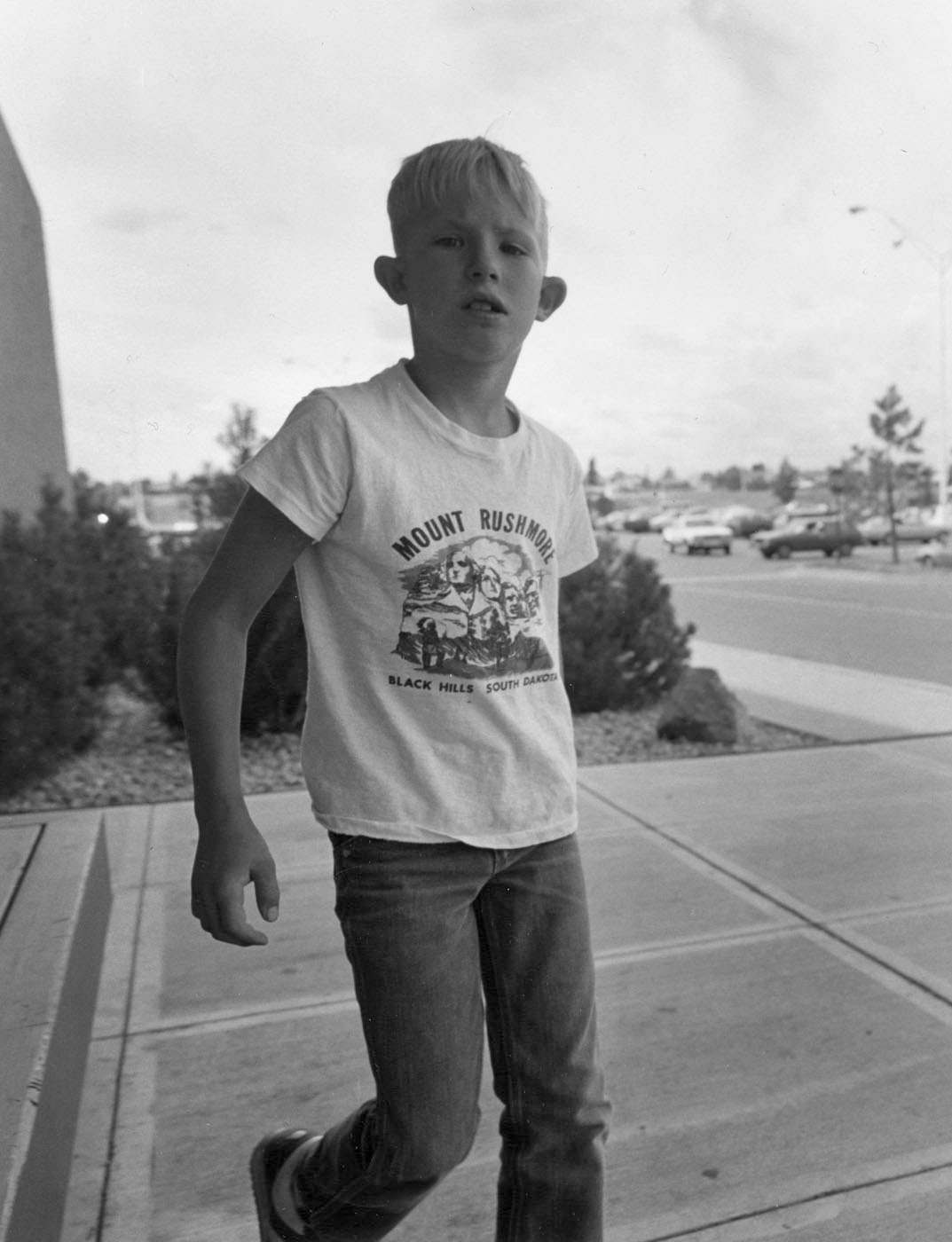

In modernist photographs that step off from Walker Evans’ legacy, Adams quiet, still photographs require of the viewer contemplation and reflection… reflection on the isolation of tract housing seemingly dropped into the vast American landscape. In these photographs (such as the two photographs Newly Occupied Tract Houses, Colorado Springs, 1968) Adams’ use of near/far is exemplary, with the nearness of the new excavation, the new scarring of the earth, contrasting with the sublime majesty of the mountains beyond. Other more personal psychological scarring can be seen in the two photographs Colorado Springs (1968-1971) where single, isolated, anonymous human beings are occluded in silhouette or shadow, damned by the hot sun.

In other photographs houses become like fossilised dinosaur skeletons, their graves marked by ironic street names such as Darwin Pl. (Frame for a Tract House, Colorado Springs, 1969), or multiply across the landscape, breeding like some genetically identical sequence (Pikes Peak Park, Colorado Springs, 1969). Even petrol stations blare out the name “Frontier” as though to irrevocably define that here we live on the edge of nowhere. And so it goes in Adams’ work… isolated people living in a barren landscape being colonised and inhabited without much thought for the beauty or the destruction of the landscape.

From the mid-1970s onwards, Adams’ landscape photographs begin to eschew all but the smallest pointers to human habitation, but this makes these human marks on the landscape all the more intrusive because of it. For example, in the photograph of the vast landscape South of the Rocky Flats Nuclear Weapons Plant, Jefferson County, Colorado (1976) the only markings of human activity are the tyre marks in the foreground and the telegraph poles, road and cars at far right… and then the title hits you with a double-whammy, “Rocky Flats Nuclear Weapons Plant”, not present in the photograph but present in our consciousness (of the landscape). Even less evidence of human existence is signalled in the photograph Missouri River, Clay County, South Dakota (1977), but then we notice at bottom left a discarded tin can, just a discarded tin can, but this one tin can says so much about our use and abuse of our only habitable planet, earth.

In image after image, roads scar the landscape, planes fly overhead, industry and housing colonise the sublime, and human beings hug and are alienated amongst concrete jungles and car parks. New development erodes the earth leaving behind the detritus of human existence. Old growth trees are slaughtered in clearcut operations in which every tree has been cut down and removed. A dead albatross rots on an expanse of beach (The Sea Beach, Albatross, 2015) while in the distance the photographer picks out 4 ghosts of human beings (The Sea Beach, 2015).

Adams’ photographic vision is extra ordinary and I cannot fault his individual photographs. I become engrossed in them. I breathe their atmosphere. He has a resolution, both in terms of large format aesthetic, the aesthetic of beauty and of using materials, light and composition… that seems exactly right. He possesses that superlative skill of few great photographers, and by that I mean: sometimes he has true compassion** / parallel to a religious compassion, but not based on something higher / just perfect human. In some of his photographs (such as East from Flagstaff Mountain, Boulder County, Colorado 1975) he possesses real forgiveness, in others there is the perfection of cruel, the perfection of de/composition.

** achieved by Arbus, Atget and sometimes by Clift, Gowin.

And then, each image holds small clues vital to the overall conversation that is the accumulation of his work and it is in their collective accumulation of meaning that Adams’ photographs grow and build to shatter not just the American silence on environmental issues, but the deafening silence of the whole industrialised world. In their holistic nature, Adams’ body of work becomes punctum and because of this his work produces other “things”, things as great as anything the French literary theorist, essayist, philosopher, critic, and semiotician Roland Barthes wrote about. As in Barthes’ seminal work Camera Lucida, Adams’ work reminds us that the “photograph is evidence of ‘what has ceased to be’. Instead of making reality solid, it reminds us of the world’s ever changing nature.”1

Human beings can never leave anything as they find it, they always have to possess and change whatever they see in a form of desecration (the action of damaging or showing no respect toward something holy or very much respected). Except human beings do not respect the only place that have to live on, this earth. When will it change?

As Alain de Botton observes on the importance of the sublime places to the human psyche,

“If the world is unfair or beyond our understanding, sublime places suggest it is not surprising things should be thus. We are the playthings of the forces that laid out the oceans and chiselled the mountains. Sublime places acknowledge limitations that we might otherwise encounter with anxiety or anger in the ordinary flow of events. It is not just nature that defies us. Human life is as overwhelming, but it is the vast spaces of nature that perhaps provide us with the finest, the most respectful reminder of all that exceeds us. If we spend time with them, they may help us to accept more graciously the great unfathomable events that molest our lives and will inevitably return us to dust.”2

We loose these places at our peril and the peril of the entire human race.

Dr Marcus Bunyan 2022

1/ Anonymous. “Roland Barthes,” on the Wikipedia website Nd [Online] Cited 23/09/2022

2/ Alain de Botton. The Art of Travel. London: Penguin, 2002, pp. 178-179.

“Robert Adams’s photographs often seem to demand that viewers do a double-take. Seemingly ordinary subjects like tree stumps, tract housing or the moon seen from a parking lot “require very careful looking and careful consideration,” says curator Sarah Greenough, before they reveal the photographer’s deeply personal visions of nature – and, sometimes, his despair at what humans have done with it.”

Peter Saenger. “Robert Adams Takes Photos That Face Facts,” on The Wall Street Journal website May 13, 2022 [Online] Cited 23/06/2022

Robert Adams (American, b. 1937)

Wheat Stubble, South of Thurman, Colorado

1965, printed 1988

Gelatin silver print

Robert Adams (American, b. 1937)

Colorado Springs

1968, printed 1983

Gelatin silver print

Robert Adams (American, b. 1937)

Burning oil sludge, north of Denver, Colorado

1973-1974

Gelatin silver print

Robert Adams (American, b. 1937)

Outdoor Theater, North Edge of Denver

1973-1974

Gelatin silver print

Robert Adams (American, b. 1937)

Cottonwood, Longmont, Colorado

1973-1975

Gelatin silver print

Robert Adams (American, b. 1937)

South of the Rocky Flats Nuclear Weapons Plant, Jefferson County, Colorado

1976

Gelatin silver print

Robert Adams (American, b. 1937)

Missouri River, Clay County, South Dakota

1977

Gelatin silver print

Robert Adams (American, b. 1937)

Larimer County, Colorado

1977

Gelatin silver print

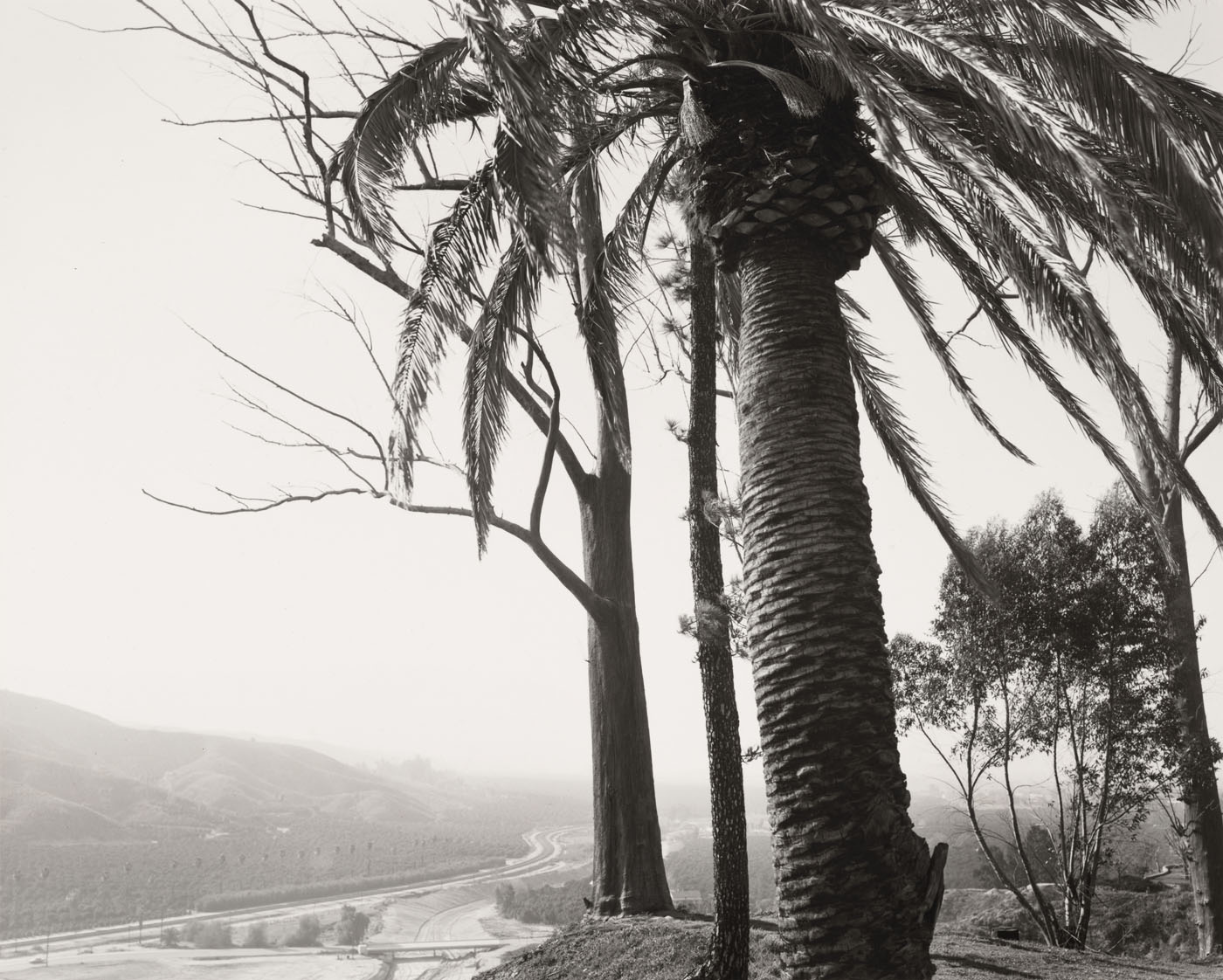

Robert Adams (American, b. 1937)

Edge of San Timoteo Canyon, Redlands, California

1978

Gelatin silver print

Robert Adams (American, b. 1937)

Nebraska State Highway 2, Box Butte County, Nebraska

1978, printed 1991

Gelatin silver print

Robert Adams (American, b. 1937)

Edge of San Timoteo Canyon, Redlands, California

1978

Gelatin silver print

Robert Adams (American, b. 1937)

Umatilla County, Oregon

1978

Gelatin silver print

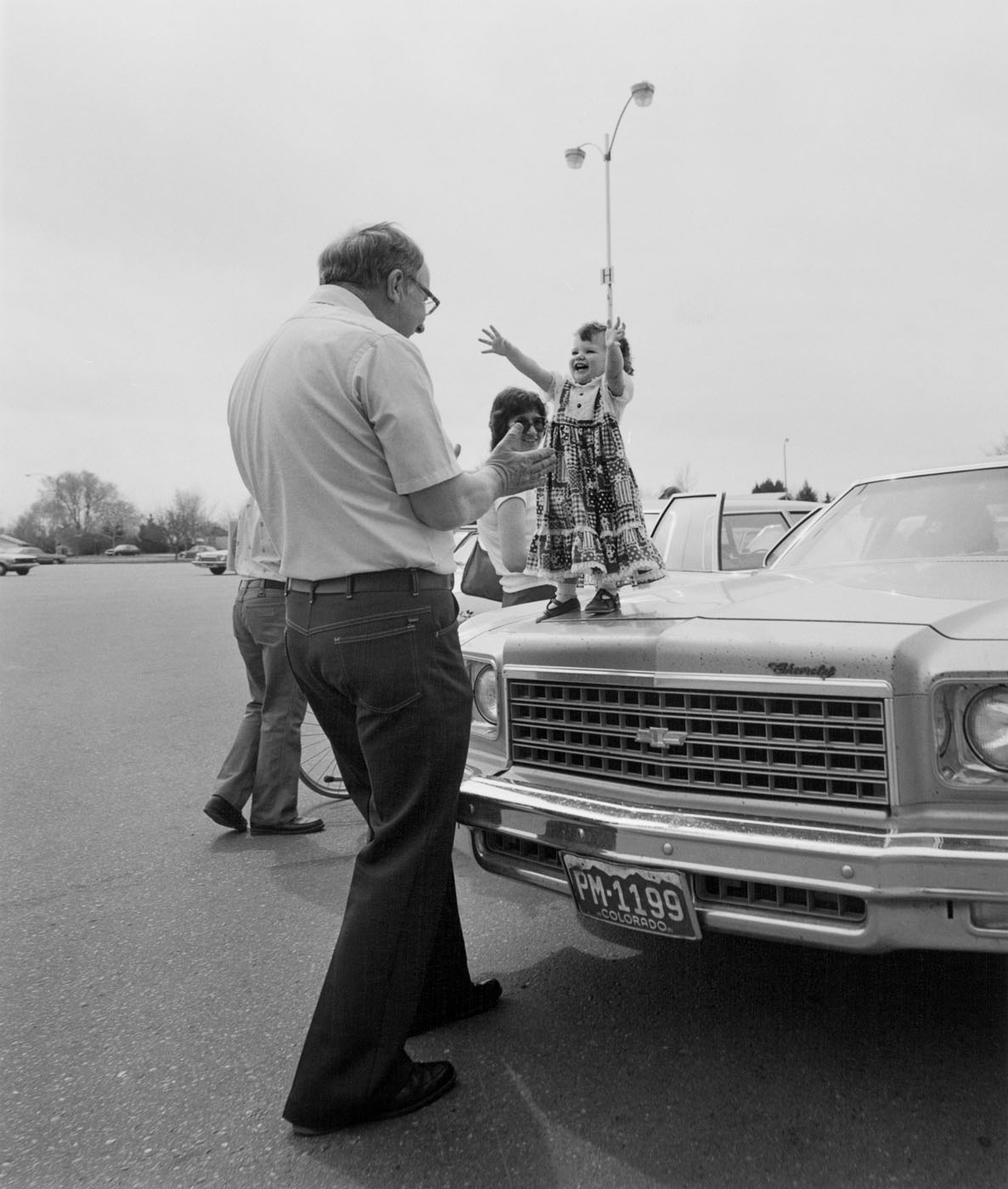

Robert Adams (American, b. 1937)

Longmont, Colorado

1979, printed 1985

Gelatin silver print

Robert Adams (American, b. 1937)

Denver

1981

Gelatin silver print

Robert Adams (American, b. 1937)

Denver

1981

Gelatin silver print

Robert Adams (American, b. 1937)

Santa Ana Wash, Redlands, California

1982

Gelatin silver print

Robert Adams (American, b. 1937)

New Development on a Former Citrus-Growing Estate, Highland, California

1983

Gelatin silver print

Robert Adams (American, b. 1937)

Broken Trees, East of Riverside, California

1983

Gelatin silver print

Robert Adams (American, b. 1937)

Baker County, Oregon

2000

Gelatin silver print

Robert Adams exhibitions and photographs on Art Blart

~ Exhibition: ‘American Silence: The Photographs of Robert Adams’ at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, May – October 2022

~ Exhibition: ‘Robert Adams: The Place We Live, a retrospective selection of photographs’ at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), March – June 2012

~ Exhibition: ‘Robert Adams: The Place We Live, A Retrospective Selection of Photographs’ at the Denver Art Museum (DAM), September 2011 – January 2012

~ Exhibition: ‘Robert Adams:

The Place We Live, A Retrospective Selection of Photographs’ at the Vancouver Art Gallery, September 2010 – January 2011